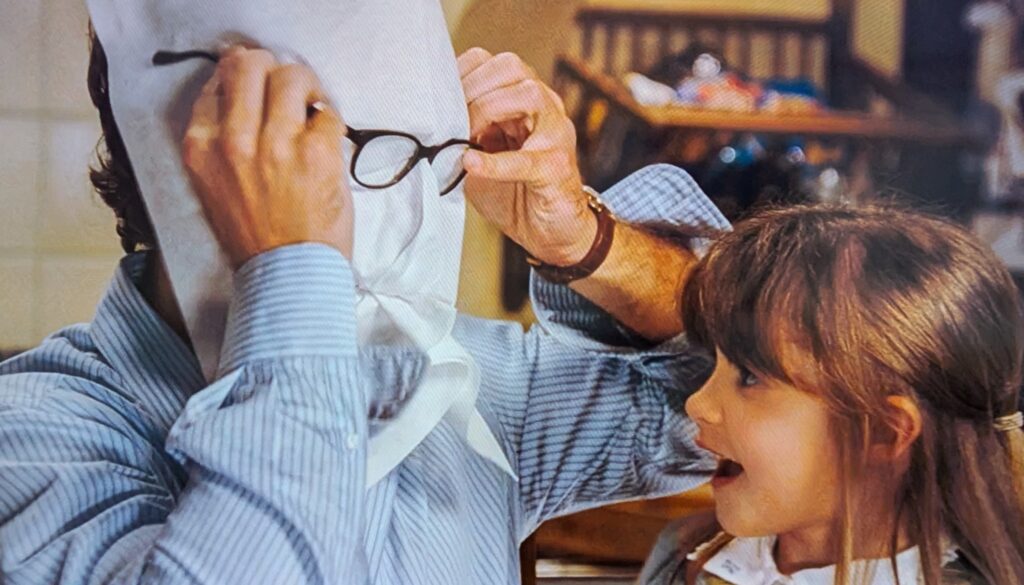

The fabulous Burt Lancaster, nearing the end of his career, plays the corporate mogul in charge of Knox Oil and Gas. Happer is incredibly eccentric; he’s obsessed with discovering and naming a comet. In Scotland Mac is to call him long distance about changes in the constellation Virgo. Lancaster brings instant gravitas to a kooky character. Casting him is excellent.

Happer is impulsive. When Mac, drunk, calls to explain the colors in the aurora borealis to him, Happer skips the pond to see for himself. He’s also wealthy and privileged, talking to Heads of State. In some ways, Happer is dotty. I prefer to see him, though, as an elderly, successful man who can do whatever he likes at this stage. He’s proven himself many times over during his career.

However, these offbeat qualities make him the best negotiator with Ben, the shack-living bum who owns the beach. Happer is excited about the sky, and Ben, who lives under the northern sky every night, is a wonderful resource. The solution they reach suits Happer’s interests, but it will also please the Knox shareholders.

Whoo, boy, the choices for his Enneagram are many. His whimsy could indicate a Seven. His charm and success could indicate a Three. His easy manner with Ben could indicate a Nine.

Lancaster was such a physical man. Remember, his career began as an acrobat. Because of this, I want to choose Nine. In “Field of Dreams” he played an elderly doctor, but we also believed that he was a remarkable baseball player in his youth. Lancaster’s real life personality touched every character he portrayed. Happer can be logically described as a Nine, but I’m picking it because . . . I gotta. It’s freakin’ Burt Lancaster.